Horse Park

More details from Thursday’s New England HBPA horse park presentation:

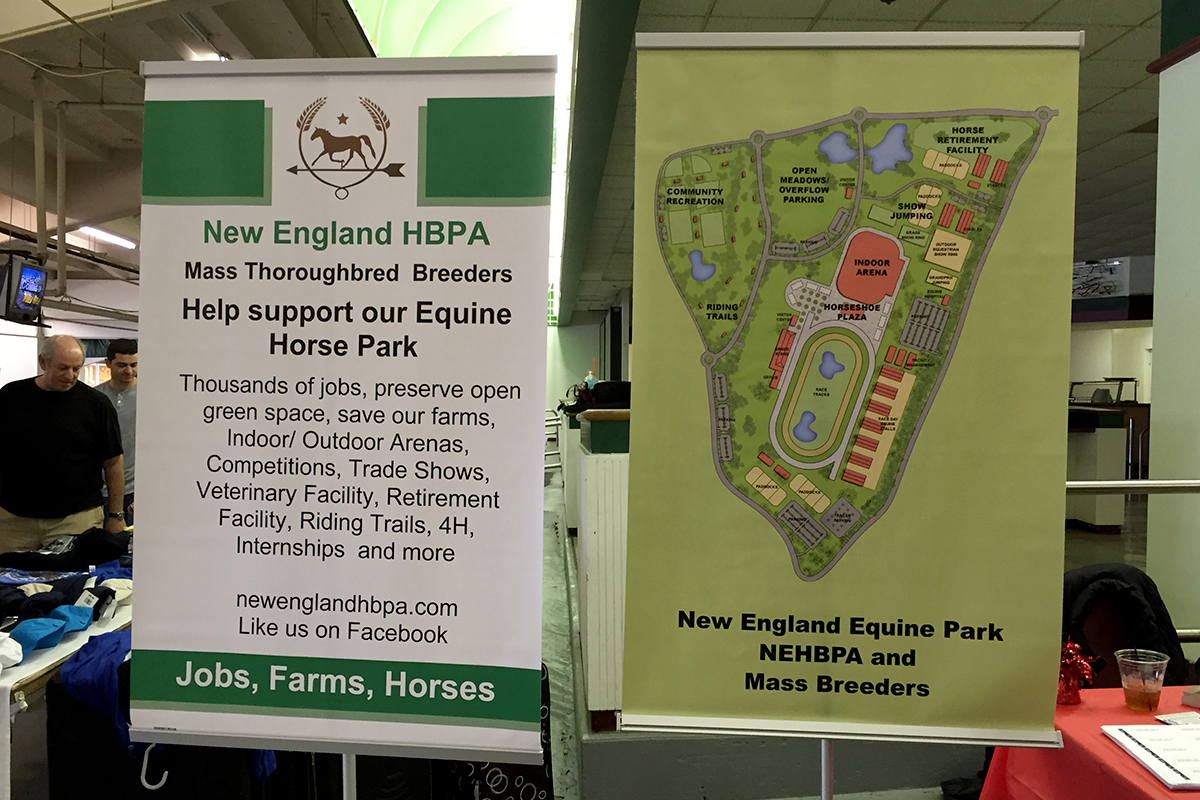

Brad Boaz, of the Lexington, Kentucky-based architectural and engineering firm CMW, gave an overview of the “Massachusetts Horse Park†master plan, as well as presented some hard numbers, during a press conference Thursday in Boston.

“Keeping the horse in mind is paramount, but also for the patron as well,†Mr. Boaz said. “We want to keep them coming back.â€

The horse park, proposed by the New England Horsemen’s Benevolent and Protective Association, would be at least 200 acres and feature a horseracing complex, an “agri-tourism village†and equestrian venues …

“We don’t feel like it’s this massive structure. It’s very quaint. It’s very inviting,†Mr. Boaz said. “What we’re trying to do is take little features from some of our most favorite tracks.â€

Saratoga was apparently cited as a model.

Let’s talk about the New England HBPA proposal for a non-profit horse park, a multi-use complex comprising a racetrack, an equestrian center, and a retirement farm. The group released a feasibility study authored by the Center for Economic Development at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst late last week (PDF), which concluded that such a facility — a “truly unique” model — would have an annual economic impact of $98.9 million on the Massachusetts economy. More than $66 million would come from the Thoroughbred racetrack, $31.7 million from the equestrian center. More details about the equestrian center and the proposal’s numbers can be found in the Blood-Horse and Daily Racing Form articles about the study.

I’m a racing fan, and what I most want to know — when Suffolk Downs is gone, and the horse park is where I have to go to get my local racing fix — is what the racing will be like. The study sketches out a simple vision:

Page 4 —

[The economic impact totals] are built on the following assumptions: 75 racing days during a typical season between May and October; 9 races per day; 800 horses in residence throughout the season; an average of 3,000 spectators per race day; and an out-of-state attendance rate of 20 percent.

Page 7 —

The center will feature a one-mile dirt oval racetrack designed for the safest possible racing of Thoroughbred horses for a 60-90 day season per year. This track could also serve as a venue for Standardbred horse racing if there is interest. Within the oval is a 7/8 mile turf course. Overlooking the track will be a viewing stand capable of seating 4,000 patrons. Within this facility will be restaurants and local wagering areas.

Page 25 —

We estimate that the new facility will attract 225,000 spectators per year … [have a] relatively smaller grandstand … a typical racing day will draw somewhere between 2,000 and 3,000 visitors, while special events (such as the MassCap) can draw up to 10,000. [The MassCap lives!]

Page 29 —

We assume that the present purse subsidies and breeding program established under the Expanded Gaming Act of 2011 will continue in their present form.

Page 30 —

[Purse and breeder incentives] will likely increase the share of Massachusetts horses racing at the new track. We use the conservative estimate that 400 active horses (or half of the assumed 800 horses on-site) will be from Massachusetts. In time, we expect an even larger share of horses racing at the new racetrack will be from in state …

So, a conventional track (aside: if you’re building a new racetrack “designed for the safest possible racing of Thoroughbred horses,” shouldn’t the main track be a turf course?), with a smaller grandstand (realistic) and a lot of Mass-bred racing supported by Race Horse Development Fund-subsidized purses.

This is an underwhelming vision, and that matters because Massachusetts racing and breeding is not isolated from the larger national market, and because financing the horse park development will depend on bonds backed by the state’s Race Horse Development Fund (legislation pending). There’s compelling public interest, in other words, in proposing a racetrack that reaches for the highest level, in the same way that the proposal does for the equestrian center, described in the report as “a first-class facility,” “capable of hosting elite national events.” Modeled on the Virginia Horse Center and Kentucky Horse Park, it’s supported by a Rolex Kentucky case study.

No racetrack case study is included in the report. There isn’t even an aspirational mention of an elite track such as Keeneland or Saratoga — although, as models, both have something to offer a new track proposal, particularly in what they do to draw spectators (one of the goals of the horse park) and to support state breeding programs and horse sales (another goal).

I don’t want to leave the impression that I’m down on the NEHBPA proposal — it’s interesting and full of potential, especially for drawing together equestrian and racing interests. But it’s an odd thing to read a study promoting a horse park for the good of horse racing (and breeding and jobs) that makes you wonder — why is there horse racing? And gives you the answer — because that’s the mechanism for accessing Race Horse Development Fund money. Horses race because the RHDF pays, the RHDF pays to keep horses racing. There’s no customer, no horseplayer, and no fan or handle growth in that perfect little circle of horsemen and state money. It’s not enough.

One other note about the study — page 30 discusses the sale of Mass-breds, and projects that out of the increased crop:

… the remaining 10 percent of foals are sold out-of-state at the national average auction price. Over the past three years, the average sale price from two-year old horses was approximately $70,000 per horse according to statistics from the U.S. Jockey Club. Thus, we include an addition $805,000 per year for expanded out-of-state horse sales.

Average prices being skewed by the market’s top end, the median price may be a better measure of how Mass-breds might do at auction. For 2-year-old horses in the past three years, the median has run around $31,000-$32,000, which would equal approximately $364,205 in expanded out-of-state sales.

1:15 PM Addition: Pedigree and sales expert Sid Fernando tweeted* about the sales assumptions in the study, adding some context to the discussion:

using a 2yo sale for projecting sales is not realistic. A yearling sale should be used, because 2yo sales are specialist events.

no one, in other words, breeds horses to sell at 2yo sales. Sellers of 2yos are usually second owners of horses.

usually state programs stimulate capital expenditure (buying stallions) by creating sire awards as adjunct to breeder awards…

…this, in turn, means more stud farms, more mares and more foals. State-bred foals are not typically commercial and have most…

…to horsemen in those programs because they race in restricted races. This stimulates local industry, for sure, but not…

…necessarily quality of horses produced because they are mostly the produce of local stallions. I think authors of paper didn’t

…have enough expertise to explain the mechanisms of all of this, good and bad, real and perceived.

economic impact to state must also capture amount of time mares are in state, for example. If a mare is sent to KY to be bred and

and returns by October, say, to qualify her resulting foal as MA-bred, that’s a mare 5 months out of state vs a mare bred to …

…local stallion. That’s why states incentivize local stallions, to keep mares in state.

He also pointed out:

btw, one area where [the study authors] underestimated economic impact: they said extra 115 foals would mean extra 115 mares, but in state …

programs fertility rates are about 50-55%, so need to effectively double mares to get 115 foals.

Additional mares would boost the estimated job and farm spending figures.

*Fernando’s account is private. He gave permission to quote the tweets above.

Copyright © 2000-2023 by Jessica Chapel. All rights reserved.