Public Spaces

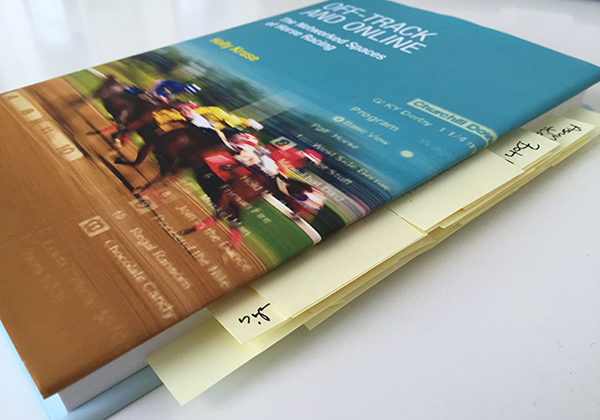

Holly Kruse’s new book, “Off-Track and Online: The Networked Spaces of Horse Racing” (MIT Press, May 2016), covers the intersections of technology, gender, class, and public spaces in horse racing. I asked Kruse about her work, the history of women in racing, and Twitter (of course) for the first issue of the Distaffer (subscribe to the newsletter).

The Distaffer: Can you talk about the genesis of “Off-Track and Online”?

Holly Kruse: I had already written about the intersection of media/technology, gender, class, and space in my previous work, including in my first book, which was about the indie music scenes. I’d also written about popular discourses of the early phonograph, and how early 20th-century discourses concerning gender and domestic space allowed the phonograph to be accepted into middle class homes. When I began looking at what was happening with horse racing and technology at the turn of this century, I was at first most interested in racing’s use of technology in public and private space. I spent much of the 1990s living in Philadelphia, where I watched the Philadelphia Park cable channel (which led to the short-lived Racing Channel), and then I moved back to Louisville just as TVG was being launched, and it was only available in Louisville. In addition, I’d spent lots of time at racetracks and was interested in how they deployed screens in public space, as well as who was in these spaces and how they were relating to each other and to the screens.

TD: You mention in the introduction that you’re puzzled more researchers don’t use horse racing as a lens for media or technology research — what’s the response you get when you discuss your work with scholarly peers?

HK: They think it’s an interesting case study. My media studies colleagues seem to think that I’ve got this covered. I hear that in the past few years there’s more media studies work being done on interactive media and gambling, and I sometimes get manuscripts to review on gambling and digital technologies. When you search databases for scholarly research on gambling, most of it seems to be on problem gambling. I think it’s good to look at how and why forms of entertainment – including gambling – are meaningful and important to people.

TD: Related, what areas of study are overlooked in horse racing and tech/media that you’re either excited about and/or would like to see explored right now?

HK: I’d like to look at online information and prediction markets, and I’m scheduled to present a paper on the topic later this year at the Association of Internet Researchers conference in Berlin. Parimutuel markets are information/prediction markets, and Betfair is the biggest company in the online prediction market game right now. Outside the U.S. Betfair allows people to bet on all kinds of questions, like whether the U.K will leave the EU. In the U.S., these kinds of prediction markets are legal if they’re educational. The oldest prediction markets are operated out of the University of Iowa: the Iowa Electronic Markets. You can invest in markets that predict the outcomes of elections, or whether the Fed will raise interest rates through the IEM.

TD: You discuss how tech affects the tribe — the way simulcasting, and more recently, ADWs, reduced cues bettors might have relied on being physically at the track and altered social information sharing in public spaces. Does social media mimic or replace the interactions bettors would have had at the track or at OTBs?

HK: I think that Twitter does this. It doesn’t replace face-to-face cues or interaction, but it may mimic it. I wouldn’t say that face-to-face or online is better or worse. Just different.

TD: I’m on Twitter way too much, and what I love about it is what you describe as “coordinated actions across space in real-time.” It gives horseplayers and fans a forum to instantly react, together, to something happening on track. But Twitter has taken a step toward being more algorithm-driven, and it seems likely that the chronological, real-time feed will go away. Just as we’ve (the racing public) reconfigured ourselves in this online space, it seems as though greater algorithmic control and more bots acting on social media and in markets means there’s another reconfiguration on the horizon.

HK: I agree, although the algorithms have always been there, just not as obvious to us. The pressure on Twitter now is to increase its number of users in order to make investors happy, and it’s been seen as a difficult platform for newbies. That’s the reason for changing Twitter so that photos and links will no longer count toward the character limit. But yeah, I disabled the “While You Where Away” feature on my Twitter feed, because I wanted to see real-time postings and chats.

TD: You trace the history of women in racing’s public spaces, from the working class spaces and “genteel” lunchrooms of 18th racetracks to the “loser” housewives at OTBs and Thoroughbred rescue activism online. I was struck by your argument with Kate Fox, whose work [“The Racing Tribe,” Transaction Publishers, May 2005] puts forward a picture of feminity at the track that’s belied by observing a typical crowd, even at tracks such as Keeneland where the dressed-up/upscale element is visible. What does this split, still a part of current industry marketing initiatives with their focus on lifestyle and fashion, mean for understanding racing’s public spaces? Are women who don’t partake in this dominant feminine/upscale narrative rendering themselves invisible as participants?

HK: That’s a good question. I think if the industry is interested in sustaining itself on the current level without solely depending on big event days or elite meets, it has to look at women and girls as multi-dimensional. But it’s also true that part of the appeal to casual fans is the idea that anyone with a pretty dress and a big hat can experience a fantasy of affluence on Derby Day, and that shouldn’t be ignored or disparaged. Racing’s appeal to women shouldn’t be only that, however.

I was thinking about how all of the humans competing in and working at the dressage schooling show that I was at last weekend were female. (With the exception of the judge and the manager of the venue.) The same would be true at a local hunter-jumper show, or in barrel racing. Reining would be the opposite, and roping. At the upper competition levels of English disciplines, where there’s serious money to be made, there are plenty of men. There’s no necessary correspondence between one’s biological sex and one’s ability to ride a horse fast around barrels: but it has been defined as a feminine sport. I don’t have a specific point to make here (or maybe I do, but it’s been a long day), except for the fact that the reasons for these distinctions are historical, social, cultural, and institutional. I point out to students in my Gender and Technology class that there’s no biological affinity between women and washing machines, or between men and lawn mowers. (Or between women and high heels.)

TD: Your mention of the dressage show and the money split between male/female participants reminded me that we see something similar among jockeys in racing — there are more female riders at the lower level, and there are tracks, such as Suffolk Downs, where female riders compete and succeed against male riders without gender appearing to be much of a factor. But the highest level of Thoroughbred racing is almost exclusively dominated by male jockeys. In her study “Gender, Work, and Harness Racing,” the sociologist Elizabeth Anne Larsen discusses this pattern in harness drivers, and how it becomes reinforcing — men are linked to good horses and success, women are not. There’s a perception issue to overcome.

HK: That’s really interesting. It’s also true in dog showing, something I’ve been doing since I was 12. At the top level, in the Group and Best in Show ring, you see a lot of professional handlers who are men. The amateurs showing dogs, however, are mostly women.

TD: In the chapter, “Social Media and Affective Networks,” you discuss how social networks have increased consciousness around the issue of Thoroughbred rescue, and “have underscored how a North American racing industry that to some degree sees racehorses as expendable has grown increasingly untenable in the twenty-first century.” This happened because of affective, uncompensated, and gendered labor — it’s the activism of women challenging an existing order. I read this, and my first thought — connecting to what you’d previously written about women in racing — was that, even though racing is largely coded as masculine, what future form racing takes is to a great extent dependent on women. What does this mean for creating space for women within environments as diverse as racetracks, OTBs, and online communities, and within the industry?

HK: I think that you’re right about the future. I think that racing has to address the lack of diversity in its positions of power, and in its offices. It doesn’t only have to do with the demographic features of the people in these spaces: it has to do with outmoded ways of thinking. When I was finishing my post-graduate certificate in the Equine Industry program at the University of Louisville, I met with several of the top executives in North American racing, thinking that I might find a job in the industry. One of them reported back to my mentor in the program that I really knew a lot about racing, but he didn’t know what he’d do with someone with a doctorate in media studies at the track. Racing has to stop replicating itself in the ways in which it’s comfortable.

TD: More generally, has social media been an effective channel for activism within racing, for instance, on issues that affect horseplayers, such as takeout?

HK: I think that you’d have to ask someone who’s been involved in organizing horseplayers to agitate for tracks to lower takeout to find out how successful social media has been. I’ve seen the discussions but don’t know if they’ve had any effect.

An underlying conflict in racing is whether it’s a sport or whether it’s gambling. If it’s the latter, then its main constituency is the horseplayers, and that’s a fairly small, but lucrative, niche. If it’s the former, then it has different issues with which it needs to engage, because members of the general public have little to no idea of what takeout is, how it varies from track to track, how it differs on exotic bets … but they do see NBC report that two horses died at Pimlico on Preakness Day, and then that shows up all over social media, and is salient to people who aren’t racing fans. Racing may be able to stay a limited, niche form of gambling, but it’s hard to see, with the increased visibility of, and concern for, animal welfare issues in general, how it can remain both.

TD: You also discuss the history of racing on TV, and it occurred to me while reading that racing and TV in the 1960s-70s was a problem of asynchronous technological development — racing couldn’t capture the success of television in handle because the network available then was so rudimentary, especially compared to the personal, mobile, connected devices we’re all carrying around now. Creating OTBs and bet-by-phone lines, as you write, were interstitial solutions. So, speculative question — what’s the tech gap now?

HK: I try to avoid these questions about tech, because who knows? It’s a problem, I think, that you can’t easily or legally stream live horse races in the U.S. unless you have an ADW account, and thus if you live in a state where ADW is legal. This is an obvious way for racing to reach a wider audience, but unless it’s tied to betting, it’s not happening. Such gaps are common in media history: the film industry suffered in the 1950s because it didn’t want to provide content to the upstart television industry; and we know what’s happened to the music industry because of its resistance to streaming.

Copyright © 2000-2023 by Jessica Chapel. All rights reserved.