Racing History

Gary West invokes (as I did on Twitter) the record of the great gelding Kelso, the only five-time Horse of the Year, in appraising Rachel Alexandra’s loss in the New Orleans Ladies Stakes last Saturday:

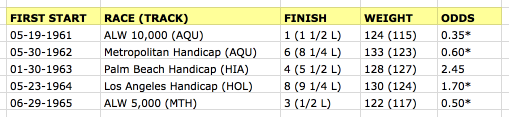

Very few horses could have performed so well returning from a six-month layoff. The effort, in fact, could have been an ideal start, a solid foundation, for an outstanding season. Kelso was named Horse of the Year five consecutive years, 1960-1964, and four times he began the following year’s campaign with a loss.

And in every year but 1964, he followed that first loss with a win. Whether Rachel Alexandra will manage the same remains to be seen, but let’s look back at Kelso, a fine example of an elite horse who was — in keeping with the times — annually raced into form without much second-guessing of either his honors or connections.

The one year Kelso won his first start back as reigning Horse of the Year was 1961, when he made his 4-year-old debut in a seven-furlong allowance race at Aqueduct, carrying 124 pounds to runner-up Gyro’s 115. “Drew out with ease,” reads the chart note.

His 1962 return in the Metropolitan Handicap was a stiffer test, with 1961 Kentucky Derby winner Carry Back among the nine starters. Carry Back, making his ninth start of the year, won brilliantly, equaling the track record time. It was the “greatest race of his career,” wrote Joseph Nichols in the New York Times of the 4-year-old’s effort. Kelso, however, coming off a lengthy layoff in which he had been recuperating from injuries suffered while finishing second in the 1961 International, was termed no threat. Carrying 133 pounds to Carry Back’s 123, the gelding “showed no inclination to run, even with Willie Shoemaker to urge him.” Of the race, Shoemaker said, “No excuses at all. That 133 pounds on him and his idleness made the difference.” In his next start, Kelso won a Belmont allowance, then finished second in the Suburban. He didn’t win his first stakes race of the year until the Stymie Handicap in September, which he followed with a win ten days later in the Woodward and another win three weeks later in the Jockey Club Gold Cup.

In 1963, off a brief eight-week rest, Kelso returned in the seven-furlong Palm Beach Handicap at Hialeah, finishing fourth to the favored Ridan, who was the runner-up to Jaipur in the 1962 Travers and a horse believed best at shorter distances. The results were considered unremarkable all around, and Kelso soundly defeated Ridan by 2 3/4 lengths in his next start two weeks later, the nine-furlong Seminole Handicap at Hialeah.

On his return in 1964, Kelso lost again, this time in the Los Angeles Handicap at Hollywood, a race in which he lugged 130 pounds to the 124 carried by winner Cyrano. “Dull effort,” notes the chart. He came back in the Californian two weeks later, finishing sixth by eight lengths as the 1.40-1 favorite.

This was the year that rumblings Kelso might be finished began, as he followed the Californian with a win in a $15,000 handicap at Aqueduct (toting 136 to the runner-up’s 114) and then seconds in the Suburban Handicap and Monmouth Handicap. In the Brooklyn Handicap, won by Gun Bow, he finished fifth by 14 lengths after stumbling badly as he came out of the starting gate. Disappointed, trainer Carl Hanford packed Kelso away for a few weeks on the farm, a respite that seemed to restore the 7-year-old gelding, who came back to win an allowance over the Aqueduct turf, and then — “in the most emotion-packed horse race since the opening of Aqueduct in 1959,” as Nichols wrote in the Times — defeated Gun Bow by three-quarters of a length in the Aqueduct Stakes, paying $6.40 to loyal backers. Second by a nose to Gun Bow in the Woodward, his next start, Kelso came back to win the Jockey Club Gold Cup by four lengths, setting two records — all-time money-earner and a new track time of 3:15 1/5 for two miles — in doing so.

From the Thoroughbred Record, November 7, 1964:

“You really think he won’t run here no more?” the fat man asked. “They said that about Carry Back and all them others, but they run again. Hell, it won’t seem like Saturday without Kelso, will it?”

Kelso was not supposed to run in 1965. The campaign he closed with an annihilating 4 1/2 length victory over Gun Bow in the 1964 International at Laurel was to be his last, but his late-season dominance had Hanford and owner Allaire duPont wavering in their plan to retire the gelding. And so Kelso, Horse of the Year for the fifth consecutive year, came back on June 29, finishing third in an allowance at Monmouth. He returned to win the Diamond State at Delaware, flashing a bit of his old form. Lightly raced that summer, the 8-year-old ended the year with an eight-length win in the Stymie on September 22, and for the first time since 1959, another horse would be named the year’s best. Or rather, two would be — Horse of the Year was shared in 1965, going to the undefeated 2-year-old filly Moccasin and Jockey Club Gold Cup winner Roman Brother.

The champion made only one more start, in a six-furlong allowance at Hialeah in March 1966 in which he finished fourth. Suffering a minor sesamoid fracture, Kelso was retired with more than $1.9 million in earnings and a career record of 63-39-12-2, his losses — and perhaps especially those incurred in his intense rivalry with Gun Bow — as much a part the story of his greatness as his many accomplishments.

Video of the 1964 International from the British Pathé archive:

From the archives: Readings: Alexander and Kelso at Aqueduct.

On the Second Pass, John Williams resurrects Joe Palmer for a new audience:

I don’t want to give the impression that an interest in the sport, or a knowledge of its history, is entirely unnecessary to an enjoyment of This Was Racing. But it’s easy enough to skim any confounding details and focus on the more universal sentiments. Like many great writers and conversationalists, Palmer mostly circled his ostensible subject, rarely landing on it. The most memorable stretches of the book aren’t about racing at all. They’re about recipes for jellied whiskey or the Australian hobby of “kangaroo chasing†or listening to a band torture “My Old Kentucky Home.†(â€I could have played it better on a comb.â€)

More than half a century removed from his work, it is good to be reminded of what a master turf writer Palmer was. Read the complete review (and then, if you haven’t, “This Was Racing”).

From the archives: An excerpt from “This Was Racing” about trainers Duval and Hal Price Headley, Menow, and the 1938 MassCap.

From the Saint Paul Daily Globe, August 10, 1892:

CHICAGO, ILL., Aug. 9. — Frances Milfred would like to be a jockey. She is from Missouri and knows how to handle a horse. Being fond of outdoor exercise and a lover of excitement, she is determined to do something besides play the typewriter or call “cash.” She is now visiting Chicago, and will not return to St. Joe unless she fails to secure a position with some owner of fast horses. It is her ambition to come down the stretch in a whipping finish and land her horse about two lengths ahead of Fox, Goodale, Overton, Penny and other slim-waisted young men who think they can ride.

Miss Milfred, after coming to Chicago a month ago, visited Washington Park and watched the flyers for several successive days. She lost $13.50 in cash ventures, but discovered a new sphere for women. The more she watched the races the more firmly she became convinced that she could learn to ride as well as any one else. Once she had been in the Kiralfy chorus and had made only $10 a week. When she heard that jockeys often made $100 for winning one race, that settled it.

Saturday evening the following “ad” appeared in one of the papers:

LADY aged twenty-five, from West, good rider, would like to learn to be a jockey. Address S. B. 84.

An encouraging letter addressed to S. B. 84 brought a reply that Miss Frances Milfred would be at home Monday at No. 17 Upton Street. There she was found, in the bottom flat, a brown-haired, slim young lady of pleasant features and a desire to explain her ambition.

“In the first place, my weight is all right,” said she. “With me it is a serious matter. I want to do something to make a living, and believe I would make a good jockey. Ever since I can remember I have been accustomed to handling horses. Four years ago I was counted the best rider in St. Joe, and once I won a race at a county fair. Do you see any reason why a young lady should not be a jockey? No. Neither do I. My folks would object, of course, but if I don’t succeed here I’m going East and try it.”

The original “jockette”?

Copyright © 2000-2023 by Jessica Chapel. All rights reserved.