Racing History

Early Kentucky Derby fave Uncle Mo has been branded by owner Mike Repole as a Great One, and in that, at this stage in the colt’s career, he’s less reminiscent of Seattle Slew — a Repole-favored comparison — than he is of Man o’ War, the most lauded horse of the early 20th century, still counted among the top three of all-time by most racing historians.

Much as the superlatives have been heaped on Mo, anointed this year’s Triple Crown hope, so the praise was on Man o’ War. The excitement for the Fair Play colt built early during his 2-year-old campaign, and was barely slowed by his famous half-length loss to Upset in the 1919 Sanford Stakes. At the end of the season, in which he went 9-for-10, often carrying a highweight of 130 pounds, the colt was deemed the greatest juvenile to have ever appeared in in the country. After Man o’ War won the 1920 Preakness Stakes, in his first start of the year, the argument began in earnest over whether he was greatest American thoroughbred ever to run, and it became something of a challenge to find starters willing to face the 3-year-old star. In his 10 starts following the Preakness, he never raced against more than three others. In several, such as the Lawrence Realization Stakes in which he set a world record of 2:40 4/5 for 1 5/8 miles, he raced against only one other.

Man o’ War, by this time frequently called “the horse of the century,” handily defeated 1919 Triple Crown winner Sir Barton in his final start, the 1920 Kenilworth Park Gold Cup, but few of his competitors from that year have names still familiar. In a bit of historical who’d-he-beat, the sparse fields of Man o’ War’s sophomore season have become reason to question his standing.

In his favor, though, Man o’ War never shirked. He was pointed to the top stakes of his time — among his wins are the Belmont Stakes, Travers Stakes, and Jockey Club Gold Cup — and he could only run against those with connections brave enough to face him. He was put into conditions to be tested. To say he was great wasn’t a mere opinion — it was a truth, as defined by what he consistently accomplished at the highest level.

With luck, Mo has many races ahead. He’s undeniably talented and fast, and his name, before long, may join the greats his record and speed so far recall. But there’s a difference between Uncle Mo and Man o’ War, between him and so many others cherished as great ones, and it’s not only his owner’s fervent, public dream for the colt’s near future, accepted by so many:

Uncle Mo may, indeed, be the next Seattle Slew and live up to the lofty expectations placed on him. The words Triple Crown were uttered here all afternoon by rival trainers, pedigree experts and breeding farm owners who are tracking the Uncle Mo camp as if they were coaches sizing up a basketball recruit. Every farm in central Kentucky wants to be the one to land the breeding deal for the first Triple Crown champion since Affirmed in 1978.

“I think the great ones know they’re great,” said Repole after Uncle Mo won the first running of the ungraded one-mile Timely Writer at Gulfstream. The great ones also prove their greatness on track, and not in races written for them.

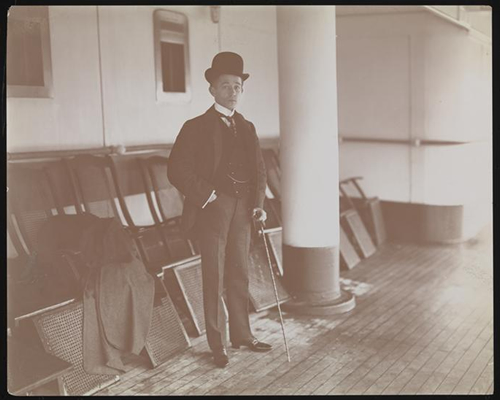

Tod Sloan, “great jockey, famed rounder, spender, one-time friend of millionaires and occasional toast of royalty,” on his return from Europe, 1898. The portrait is part of the Museum of the City of New York’s photography collection, much of which was recently published online. A quick search turns up approximately 150 photos of New York racing — including Sheepshead and Belmont racetracks — from the late 19th and early 20th century (via Kottke).

Frank Mitchell asks, “who are the great mares of the past 100 years?” Coming up with names isn’t a problem (there are so many), but refining the ranking methodology could be tricky. Record in open company has to be one of the criteria. Regarding that, you have to give Alan Shuback credit for pointing out the unpopular fact that, as the two near their final races in the Breeders’ Cup, Goldikova has proved more than Zenyatta.

The Racing Post rates Dewhurst winner Frankel “as the best European juvenile in the 21st century.” On the all-time list, he ties for third. No doubt Frankel’s freaky, and so is Champagne winner Uncle Mo, as measured by Thorograph. [More Frankel: BHA handicapper Mathew Tester bumps his rating up to 124. That’s the second highest for a Dewhurst winner this young century. It’s also second for the season to Dream Ahead’s top-rated nine-length Middle Park win, and as such, “doesn’t do justice” to the colt, sniffs Hotspur.]

The Breeders’ Cup Juvenile Fillies lost one contender and gained another over the weekend. Oak Leaf winner Rigoletta has been ruled out with a splint injury. Undefeated homebred Awesome Feather earned herself a shot at Churchill Downs after winning the My Dear Girl division of the Florida Stallion Stakes at Calder. “Breeders’ Cup!,” exulted owner-trainer Stanley Gold. “That’s what we discussed going into the race. If she won and did it right, we’d go …”

So, I guess this guy plays football? And he visited Zenyatta?

Copyright © 2000-2023 by Jessica Chapel. All rights reserved.