Not So Slow

Left at the Gate posted a Preakness Stakes pace analysis that you should read in full, but the upshot is that on a slow track Oxbow:

… was a running fool and bottomed them all out, the way I see it.

Which is why Oxbow’s Preakness Beyer speed figure is 106, something Bill Oppenheim writes about in today’s Thoroughbred Daily News:

When I first saw the time of Saturday’s Preakness S. — 1:57:2/5, the slowest in 51 years … I thought the Beyer speed figure was sure to come back in the nineties. But when I looked at the times for the other dirt races — 1:10 and change for two six-furlong stakes, and 1:46 and change for and older filly-and-mare Grade III — it did look like the track was slow, and Andy Beyer confirmed there was a stiff headwind against the horses in the stretch.

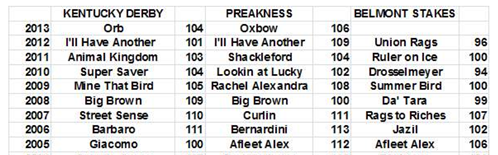

Oppenheim also publishes a table (PDF), with data provided by Andrew Beyer, of the Beyer speed figures for all the Triple Crown races from 1987 to 2013 (minus this year’s Belmont Stakes, of course), documenting the decline in figures over those years, and in particular, the sharp decline in figures over the past five years, especially in the Belmont Stakes. “That has to be the result of lack of stamina in pedigrees,” Beyer tells Oppenheim.

Trends in breeding can’t be ignored, but the data suggest that there may be additional factors at work, such as changing training practices and the elimination of routine steroid use. If you look at the Belmont Stakes figures, until 2005, the Belmont speed figures are generally in line with or higher than the figures for the Kentucky Derby and Preakness. Starting in 2006, the Belmont Stakes figure is consistently lower than both the Kentucky Derby and the Preakness figures; from 2006-2012, no Belmont winner earns a higher Beyer than the winner of the Derby or the Preakness.

The most striking thing about the table, though, is that Belmont Stakes figures essentially collapse in 2008. That was the year Da’Tara earned a 99 after Big Brown faltered; no winner has been given better than 100 since. It may be chance, but the period beginning with 2006 coincides with a fresh-is-best training approach to the Triple Crown and a string of Kentucky Derby winners with two preps, and the period beginning with 2008 coincides with a Kentucky Derby winner weaned off Winstrol and an industry-wide steroids ban.

3:45 PM Addendum: Dick Jerardi explains how the 106 given Oxbow was determined: “The key horse in the Preakness was Itsmyluckyday …” (He was given a Beyer of 103 for finishing second.)

Tarnished Encke

The British Horseracing Authority released on Monday the results of tests done on all Godolphin-owned racehorses based in Newmarket, revealing that seven additional horses trained by the now-suspended Mahmood al Zarooni turned up positive for steroids — including the 2012 St. Leger winner Encke. That name atop the list was explosive, immediately raising the question of whether Camelot, second in the St. Leger, lost the Triple Crown to a horse who may have been treated with banned substances. Encke tested clean before and after the race last September, but the question will linger, writes Greg Wood:

And, thanks to the poisonous nature of anabolic steroids, which leave suspicions lingering when all traces of the drug have gone, it is a question that will probably never have an answer.

For Paul Hayward, Encke’s positive:

is a disaster all by itself. It casts doubt on a whole season of Flat racing and requires an asterisk to be placed next to the final Classic of 2012.

Encke will not be disqualified, said the BHA. “There is absolutely no evidence at all that [he] was gaining benefit from prohibited substances in the St Leger.”

It’s a determination that must be accepted, unless new details emerge about Zarooni’s operation at Moulton Paddocks (the investigation is ongoing).

American racing fans know the uncertainty, even if the situations are different: Big Brown’s 2008 run for the Triple Crown, and his baffling performance in the Belmont Stakes, was also clouded by the issue of (then legal) steroids.

Orb and Swale

Post-Preakness, Marc Attenberg started a conversation on Twitter about the historical significance of Orb’s off-the-board finish by asking:

Last time a sub even-money Derby winner failed to hit the board in the Preakness? Not in 20 years or more? Anyone got the answer?

Swale was the answer. The 1984 Kentucky Derby winner, running second for much of the Preakness to pacesetter Fight Over (who held on for third), failed to kick in the stretch and finished seventh as the 4-5 favorite, beaten seven lengths by Gate Dancer (fifth in the Kentucky Derby*). Steven Crist, reporting for the New York Times, described Swale’s stunning defeat as:

the worst by any odds-on favorite in the history of the Preakness and the worst by any favorite since First Landing finished ninth in 1959.

No excuses were made for Swale, who would win the Belmont Stakes. “It was the consensus of most of us in the barn,” the colt’s groom Michael Klein wrote in his memoir, Track Conditions:

that Swale was running the race only because the Preakness was a jewel in the Crown, and to fulfill a theoretical obligation, he had to make a showing. The last jewel — the Belmont Stakes — was much more to his taste, both in terms of distance and quality of racing surface.

We’ll find out in a little less than three weeks, if Orb starts in the Belmont, whether the same can be said of him.

Below, Preakness winners and beaten Kentucky Derby winners, 1984-2013:

Preakness winners 1984-2013, where they finished in the Kentucky Derby, and their Preakness odds / Kentucky Derby winners, where they finished in the Preakness, and their Preakness odds / * = Preakness post-time favorite

Worth noting — Oxbow is the highest-priced Preakness winner of the past 30 years, confirming that the second leg of the Triple Crown hasn’t been the best race to look for longshots (the Belmont, though, is another matter).

*Fourth, actually, but the eccentric colt was disqualified and placed fifth for interference. It was the first DQ in Kentucky Derby history.

Copyright © 2000-2023 by Jessica Chapel. All rights reserved.