NEHBPA

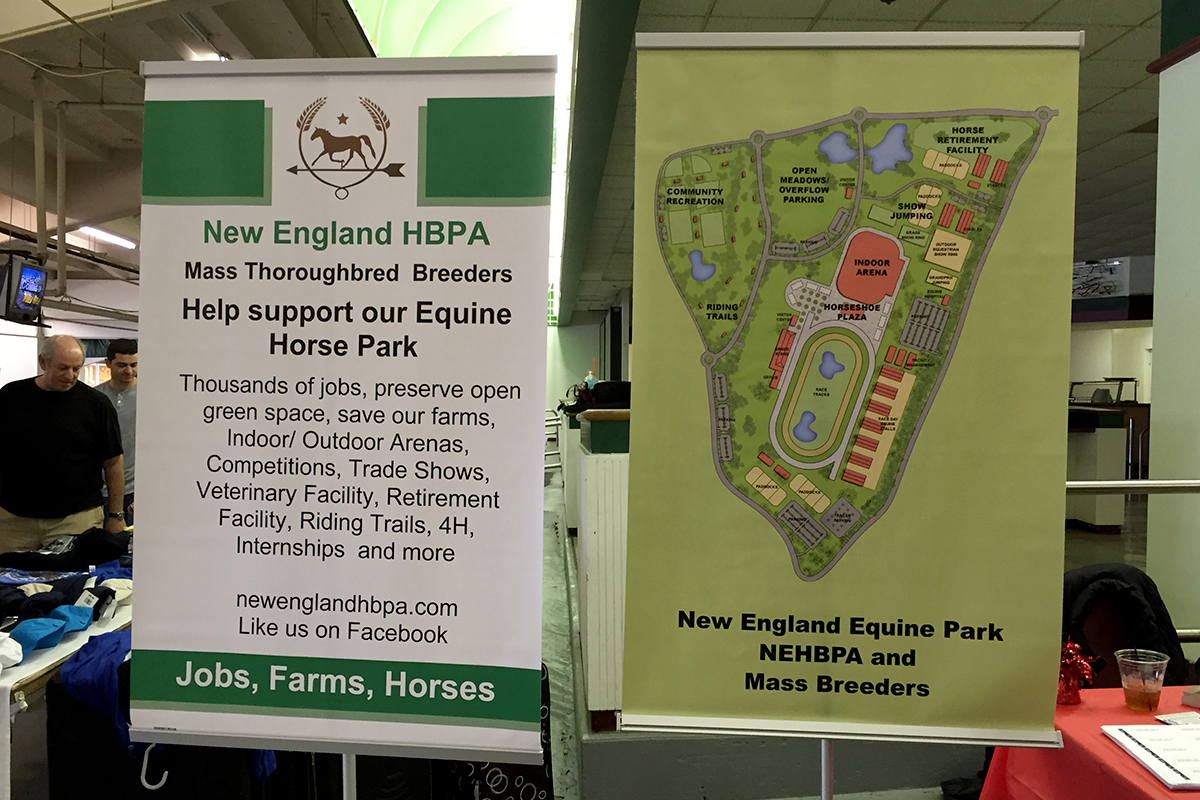

More details from Thursday’s New England HBPA horse park presentation:

Brad Boaz, of the Lexington, Kentucky-based architectural and engineering firm CMW, gave an overview of the “Massachusetts Horse Park†master plan, as well as presented some hard numbers, during a press conference Thursday in Boston.

“Keeping the horse in mind is paramount, but also for the patron as well,†Mr. Boaz said. “We want to keep them coming back.â€

The horse park, proposed by the New England Horsemen’s Benevolent and Protective Association, would be at least 200 acres and feature a horseracing complex, an “agri-tourism village†and equestrian venues …

“We don’t feel like it’s this massive structure. It’s very quaint. It’s very inviting,†Mr. Boaz said. “What we’re trying to do is take little features from some of our most favorite tracks.â€

Saratoga was apparently cited as a model.

The State House News Service reported on Tuesday that a section of the 2018 budget proposal in the Massachusetts state senate would sweep $15 million from the Race Horse Development Fund into the state general fund:

“It’s just been sitting there,” Senate Ways and Means Chairwoman Karen Spilka said of the Race Horse Development Fund money Tuesday. “That’s where we give some of the increases to (the Department of Environmental Protection) and (the Department of Conservation and Recreation). We use it for conservation and recreation, consistent with the original purpose.”

“Much of the fund’s assets have remained unused, and given the state’s tight fiscal situation, we direct the money to protect and enhance our natural resources for the benefit of residents across Massachusetts.”

This development is no surprise. With Thoroughbred racing scheduled for six days this year and the recent sale of Suffolk Downs putting a likely end to any racing after 2018, there’s a growing pool of money in the RHDF with nowhere to go. The fund, collecting 9% of the slots revenue at Plainridge, had a balance of approximately $15.6 million through April. Last month, a Boston Globe editorial called for a new mission for the RHDF millions:

When the casino law was passed, allies of the racing industry tried to spin the fund as something other than a special-interest giveaway by claiming it served the broader public interest in preserving open space on horse farms.

If preservation is really Beacon Hill’s concern, though, it would make more sense to follow the suggestion of State Representative Bradley H. Jones, a Republican from North Reading, who last year proposed redirecting some of the horse racing money into community preservation funding for municipalities. Community Preservation Act money can be used for open space, affordable housing, and historic preservation; local dollars are supposed to be matched with state money, but the state’s contribution has been declining in recent years and will be stretched even thinner now that Boston voted to join the program …

Jones’s proposal would be a step in the right direction, but the state’s ultimate goal should be to wean horse racing off state support completely. The collapse of horse racing has inflicted undeniable pain on many workers in Massachusetts, and they deserve the Commonwealth’s full support making a transition to more viable jobs. But simply paying them to run horses in front of ever-shrinking crowds — at Suffolk Downs, in New York, or anywhere else — is not a long-term economic policy.

A review of the fund’s work by The Eye and WBUR public radio has found scant gains in breeding race horses, a schedule of racing that continues to be limited, and growing infighting among industry factions that has tried the patience of the fund’s overseers.

And I wrote in 2014 that the legislature would come for the RHDF.

Much like last year’s revised split that increased standardbreds’ share of the RHDF from 25% to 55% — Plainridge is running 125 days with average daily purses of $60K and a $250,000 stakes race in 2017 thanks to the boost — the proposed appropriation in the 2018 budget bill is being sold as a temporary way to put the fund to use — it’s for one fiscal year only — except that legislators, whether or not the budget passes as currently written, aren’t likely to forget that the RHDF money is there. The fund will become an even more tempting target for raids when the Springfield MGM casino opens in 2018 and a percent of its revenue begins to swell the RHDF.

New England HBPA executives promise to fight the proposed appropriation:

The New England Horsemen’s Benevolent and Protective Association, for example, makes the case that the money in the fund was intended to promote horse racing. What better way to promote horse racing than to promote a horse park with a track, officials said.

“When we look at that money in the Horse Race Development Fund, we see 1,000 jobs and the preservation of open space,†said Paul Umbrello, executive director of the horsemen’s association. “We will fight the transfer.â€

The NEHBPA continues to push their horse park plan; they propose to build a new racetrack and equestrian center in Spencer, a small town in central Massachusetts that’s off the Mass Pike but more than an hour from Boston. It’s a longshot. The Boston Herald blasted the plan a few weeks ago:

Now, silly us for raising a question like this, but if Suffolk Downs couldn’t make a go of thoroughbred racing a stone’s throw from downtown Boston, why on earth would the state want to invest its money in such a venture, say in maybe a town like Spencer?

It was, after all, Sen. Anne Gobi (D-Spencer) who filed a bill to divert money from the fund to a horse race park, while acknowledging that the racing industry is “on life support.â€

“This is an opportunity to support the entire industry,†she added. “We have to do something because it’s going and once it’s gone it’s not coming back.â€

And calling horse racing an “industry†does not make it so.

“We just want to say we want to take X percentage of that fund to build and support, as a bridge gap, the horse park,†Umbrello said. “Once we’re up and running it’s going to be self-sufficient.â€

Like we’ve never heard that one before!

Until lawmakers find a better use for the racing fund it will continue to attract nutty schemes like this one.

(My initial reaction to the NEHBPA plan when it was laid out last summer.)

The Massachusetts Gaming Commission declined to comment earlier this week, but chairman Stephen Crosby told the Globe last month that while:

he supported legislation that would reform the horse racing industry and give it a better chance of success in Massachusetts … taking away the fund would be the “death knell†for racing in the Commonwealth.

The death knell is sounding — the obstacles to the NEHBPA horse park are substantial, Brockton is not viable, and the state of the larger racing industry is against new construction or a new track operator entering Massachusetts.

8:00 PM Addendum: The NEHBPA pitched the horse park to reporters in an event this afternoon, Bruce Mohl reports in CommonWealth:

Brian Hickey, the association’s lobbyist and the host of Thursday’s presentation, said the group would like to see the law changed so the money in the Horse Race Development Fund could be used to directly support the state’s horse-racing industry. He estimated a couple hundred thousand dollars would be needed for the horse park feasibility study, and indicated more of the money would be needed if the horse park itself moves forward. He said revenues from simulcasting races from around the country could also be used to support the park.

More to come …

Let’s talk about the New England HBPA proposal for a non-profit horse park, a multi-use complex comprising a racetrack, an equestrian center, and a retirement farm. The group released a feasibility study authored by the Center for Economic Development at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst late last week (PDF), which concluded that such a facility — a “truly unique” model — would have an annual economic impact of $98.9 million on the Massachusetts economy. More than $66 million would come from the Thoroughbred racetrack, $31.7 million from the equestrian center. More details about the equestrian center and the proposal’s numbers can be found in the Blood-Horse and Daily Racing Form articles about the study.

I’m a racing fan, and what I most want to know — when Suffolk Downs is gone, and the horse park is where I have to go to get my local racing fix — is what the racing will be like. The study sketches out a simple vision:

Page 4 —

[The economic impact totals] are built on the following assumptions: 75 racing days during a typical season between May and October; 9 races per day; 800 horses in residence throughout the season; an average of 3,000 spectators per race day; and an out-of-state attendance rate of 20 percent.

Page 7 —

The center will feature a one-mile dirt oval racetrack designed for the safest possible racing of Thoroughbred horses for a 60-90 day season per year. This track could also serve as a venue for Standardbred horse racing if there is interest. Within the oval is a 7/8 mile turf course. Overlooking the track will be a viewing stand capable of seating 4,000 patrons. Within this facility will be restaurants and local wagering areas.

Page 25 —

We estimate that the new facility will attract 225,000 spectators per year … [have a] relatively smaller grandstand … a typical racing day will draw somewhere between 2,000 and 3,000 visitors, while special events (such as the MassCap) can draw up to 10,000. [The MassCap lives!]

Page 29 —

We assume that the present purse subsidies and breeding program established under the Expanded Gaming Act of 2011 will continue in their present form.

Page 30 —

[Purse and breeder incentives] will likely increase the share of Massachusetts horses racing at the new track. We use the conservative estimate that 400 active horses (or half of the assumed 800 horses on-site) will be from Massachusetts. In time, we expect an even larger share of horses racing at the new racetrack will be from in state …

So, a conventional track (aside: if you’re building a new racetrack “designed for the safest possible racing of Thoroughbred horses,” shouldn’t the main track be a turf course?), with a smaller grandstand (realistic) and a lot of Mass-bred racing supported by Race Horse Development Fund-subsidized purses.

This is an underwhelming vision, and that matters because Massachusetts racing and breeding is not isolated from the larger national market, and because financing the horse park development will depend on bonds backed by the state’s Race Horse Development Fund (legislation pending). There’s compelling public interest, in other words, in proposing a racetrack that reaches for the highest level, in the same way that the proposal does for the equestrian center, described in the report as “a first-class facility,” “capable of hosting elite national events.” Modeled on the Virginia Horse Center and Kentucky Horse Park, it’s supported by a Rolex Kentucky case study.

No racetrack case study is included in the report. There isn’t even an aspirational mention of an elite track such as Keeneland or Saratoga — although, as models, both have something to offer a new track proposal, particularly in what they do to draw spectators (one of the goals of the horse park) and to support state breeding programs and horse sales (another goal).

I don’t want to leave the impression that I’m down on the NEHBPA proposal — it’s interesting and full of potential, especially for drawing together equestrian and racing interests. But it’s an odd thing to read a study promoting a horse park for the good of horse racing (and breeding and jobs) that makes you wonder — why is there horse racing? And gives you the answer — because that’s the mechanism for accessing Race Horse Development Fund money. Horses race because the RHDF pays, the RHDF pays to keep horses racing. There’s no customer, no horseplayer, and no fan or handle growth in that perfect little circle of horsemen and state money. It’s not enough.

One other note about the study — page 30 discusses the sale of Mass-breds, and projects that out of the increased crop:

… the remaining 10 percent of foals are sold out-of-state at the national average auction price. Over the past three years, the average sale price from two-year old horses was approximately $70,000 per horse according to statistics from the U.S. Jockey Club. Thus, we include an addition $805,000 per year for expanded out-of-state horse sales.

Average prices being skewed by the market’s top end, the median price may be a better measure of how Mass-breds might do at auction. For 2-year-old horses in the past three years, the median has run around $31,000-$32,000, which would equal approximately $364,205 in expanded out-of-state sales.

1:15 PM Addition: Pedigree and sales expert Sid Fernando tweeted* about the sales assumptions in the study, adding some context to the discussion:

using a 2yo sale for projecting sales is not realistic. A yearling sale should be used, because 2yo sales are specialist events.

no one, in other words, breeds horses to sell at 2yo sales. Sellers of 2yos are usually second owners of horses.

usually state programs stimulate capital expenditure (buying stallions) by creating sire awards as adjunct to breeder awards…

…this, in turn, means more stud farms, more mares and more foals. State-bred foals are not typically commercial and have most…

…to horsemen in those programs because they race in restricted races. This stimulates local industry, for sure, but not…

…necessarily quality of horses produced because they are mostly the produce of local stallions. I think authors of paper didn’t

…have enough expertise to explain the mechanisms of all of this, good and bad, real and perceived.

economic impact to state must also capture amount of time mares are in state, for example. If a mare is sent to KY to be bred and

and returns by October, say, to qualify her resulting foal as MA-bred, that’s a mare 5 months out of state vs a mare bred to …

…local stallion. That’s why states incentivize local stallions, to keep mares in state.

He also pointed out:

btw, one area where [the study authors] underestimated economic impact: they said extra 115 foals would mean extra 115 mares, but in state …

programs fertility rates are about 50-55%, so need to effectively double mares to get 115 foals.

Additional mares would boost the estimated job and farm spending figures.

*Fernando’s account is private. He gave permission to quote the tweets above.

Copyright © 2000-2023 by Jessica Chapel. All rights reserved.