Suffolk Downs

If I had to choose a moment to remember from the last weekend of racing at Suffolk Downs what would it be? It could be T.D. Thornton’s final call:

“They approach the quarter pole in the grand finale and they turn into the Suffolk Downs homestretch for the final time … 84 years of history behind them, half a furlong to the finish, and it’s all Catauga County, by seven on the line. Admiration was second, Shiloh Lane was third. Wow! What a long run it’s been, what a wild ride since 1935. Thanks, Suffolk Downs, for a lifetime of great memories!”

It could be paddock analyst Jessica Paquette’s heartfelt goodbye from the scale house roof before the horses left the paddock for the last time.

Or it could be the thunderstorm on Saturday that left the lights flickering in the grandstand and forced the cancellation of the last three races scheduled that day, including the $100,000 James B. Moseley Stakes — which, had it happened, would have honored the man who led the revival of the track in 1992 from a two-year shuttering. In the post-mortem, let it be noted that in its last days, the track remembered its history, recent and long past.

It could be the unexpected sight of a memorial near the winner’s circle, three people standing at the rail, a man shaking out ashes from a bag into the track’s dirt before they crossed themselves and prayed.

Or maybe the woman who, picking her way through puddles, sandals dangling from her hand, cried, “This is the last time I’ll walk barefoot across this track!” As if it were something she did many times. And who knows? Maybe she did. A lot can happen in 84 years, and a lot happened at Suffolk Downs. Tom Smith discovered Seabiscuit. Bill Mott brought Cigar to Boston to win the Mass Cap in 1995 and 1996. Waquoit made his hometown proud in the 1987 Mass Cap.

Those are the high points. Everyone knows them. Most of what happened at Suffolk Downs happened out of the spotlight — it happened to the families who bred and trained horses and worked the grandstand and the backstretch for generations. It happened to the women who wanted to be jockeys and found a track where they could get a foothold. It happened to the kid who came to the track with his dad and then snuck in as a teenager and then made a career in the game. It happened to the young-ish woman who went to Suffolk one day and found the beauty and meaning that so many had before in horses and handicapping. (Am I getting weepy right now? I might be.)

But the moment that I might choose would be the sound of the crowd cheering when the field for the fifth race on Sunday went to the gate after another storm delay. The rain might have chased some people away, but most of the crowd jammed into the grandstand seats and waited the downpour out. They roared and clapped and whooped when the bugle sounded and the horses began to leave the paddock. For a second, the grandstand was a wall of sound, what it was when I went to my first Mass Cap in 2004 and Offlee Wild nipped Funny Cide for the win, what it must have been for so many races before.

It was the sound of people at the track, happy to be there.

Photos from the final weekend at Suffolk Downs:

A dream comes true for Jessica Paquette, who rode New England champion — and very good pony — Mr. Meso into the paddock on Saturday and delivered her analysis of the day’s first race from the saddle.

Tammi Piermarini and Saint Alfred (inside) outrun Luis Quinones and Desert Dotty to win the Thomas F. Moran Stakes for Massachusetts-breds on Sunday.

Piermarini and Saint Alfred galloping back after winning the Moran. At the end of Suffolk’s six-day meet, Piermarini topped the track’s jockey standings once again (and for the last time), with 10 wins and $347,650 in earnings.

J.D. Acosta, second in the standings with eight wins and earnings of $317,550.

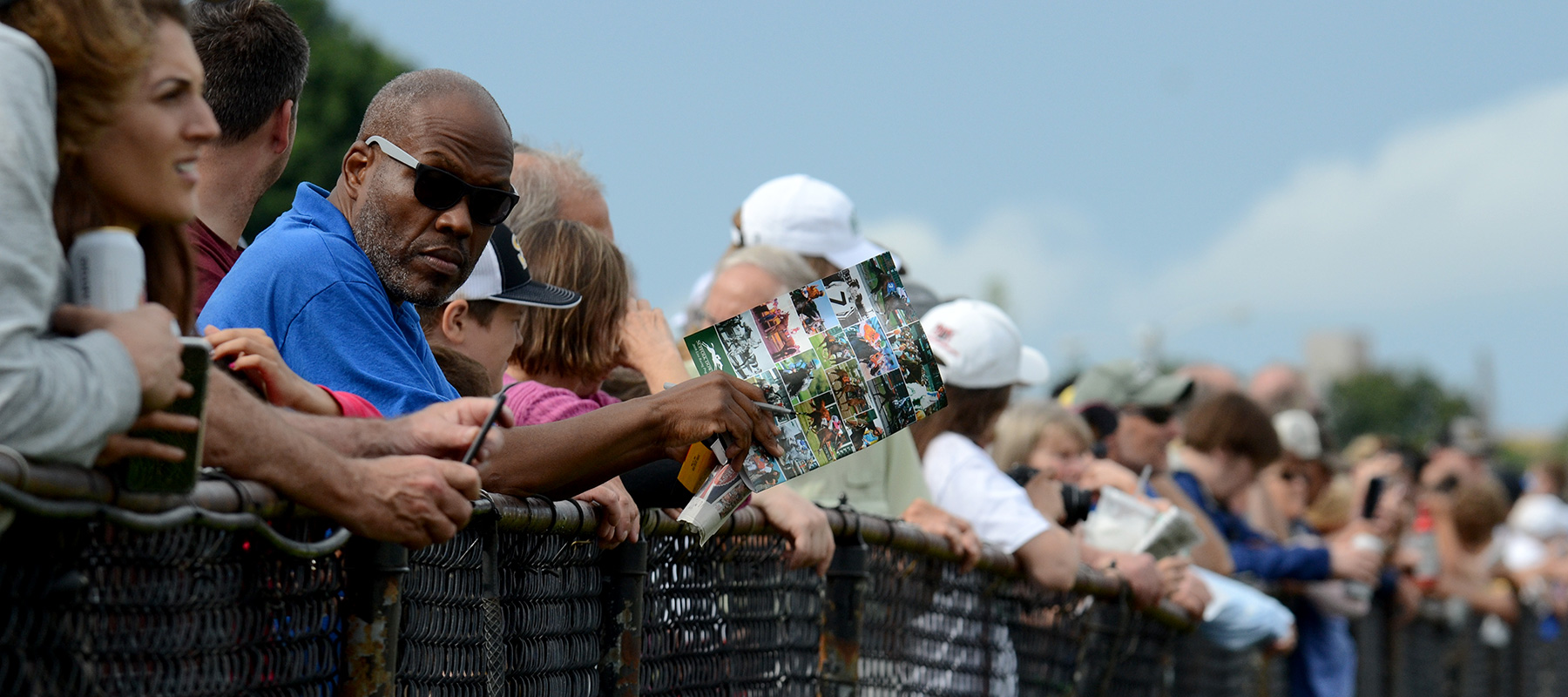

The crowd on the grandstand rail. An estimated 12,311 attended the races on Sunday; the figure for both days was estimated at more than 21,000.

A thunderstorm delayed the start of the fifth race on Sunday.

A reflection in the scale house window of a horse being unsaddled.

The Sunday crowd along the clubhouse rail.

Dirt flies up as the field for race 10 on Sunday — the final race — runs past the finish line for the first time and toward the clubhouse turn.

Maiden no more, and now a name for racing history: Catauga County, with rider Andy Hernandez Sanchez, wins the last race at Suffolk Downs.

Catauga County returns to the winner’s circle for trainer Neil Morris and owner PathFinder Racing. The 4-year-old Violence gelding paid $5.60 to win.

Signing autographs, taking selfies: Hernandez Sanchez finds himself popular with the Suffolk fans after winning the track’s last race.

People walked across the track after racing was done to take photos — and to get their photos taken in front of the infield tote board.

I tweeted last week about working on the backstretch at Suffolk Downs and Saratoga several years ago, something I’ve talked about here and there before. My time as a hotwalker was a rich experience — I’ll always be glad I did it, not least because it gave me a glimpse behind the scenes and another perspective on racing that still informs my involvement as a fan and bettor.

What led to the thread on Twitter was trainer Gary Contessa’s quoted remarks from the Albany Law School’s Saratoga Institute on Equine, Racing, and Gaming Law Conference. “Nobody in America wants this job,” he said of working on the backstretch and the need for immigrant labor. I wanted to push back on the idea that the fault mostly lies with workers, which is how the issue often seems portrayed to me, letting owners and trainers dodge responsibility for working and living conditions that can be onerous.

I expanded the tweets into an opinion piece for the Thoroughbred Daily News, and now that it’s out there, I have a couple of things to add:

I refer to “passion” toward the end in a half-formed thought. Embedded in that mention was a criticism of how the word gets (ab)used, and not just by people in racing — “passion” for work is everywhere these days, and it sometimes gets twisted to mean that if you’re passionate about work, you’ll tolerate every demand it makes, which is handy for employers — reject some terms, and the problem isn’t with the work, it’s with you, and your lack of passion.

If anything comes of writing this piece, I hope it’s that more stories about working on the backstretch get told, from all different perspectives — major circuits and big barns, small tracks and family-run operations, immigrant and non-immigrant. I also hope it might lead to a constructive conversation about working conditions, backstretch culture, and resources for workers.

The State House News Service reported on Tuesday that a section of the 2018 budget proposal in the Massachusetts state senate would sweep $15 million from the Race Horse Development Fund into the state general fund:

“It’s just been sitting there,” Senate Ways and Means Chairwoman Karen Spilka said of the Race Horse Development Fund money Tuesday. “That’s where we give some of the increases to (the Department of Environmental Protection) and (the Department of Conservation and Recreation). We use it for conservation and recreation, consistent with the original purpose.”

“Much of the fund’s assets have remained unused, and given the state’s tight fiscal situation, we direct the money to protect and enhance our natural resources for the benefit of residents across Massachusetts.”

This development is no surprise. With Thoroughbred racing scheduled for six days this year and the recent sale of Suffolk Downs putting a likely end to any racing after 2018, there’s a growing pool of money in the RHDF with nowhere to go. The fund, collecting 9% of the slots revenue at Plainridge, had a balance of approximately $15.6 million through April. Last month, a Boston Globe editorial called for a new mission for the RHDF millions:

When the casino law was passed, allies of the racing industry tried to spin the fund as something other than a special-interest giveaway by claiming it served the broader public interest in preserving open space on horse farms.

If preservation is really Beacon Hill’s concern, though, it would make more sense to follow the suggestion of State Representative Bradley H. Jones, a Republican from North Reading, who last year proposed redirecting some of the horse racing money into community preservation funding for municipalities. Community Preservation Act money can be used for open space, affordable housing, and historic preservation; local dollars are supposed to be matched with state money, but the state’s contribution has been declining in recent years and will be stretched even thinner now that Boston voted to join the program …

Jones’s proposal would be a step in the right direction, but the state’s ultimate goal should be to wean horse racing off state support completely. The collapse of horse racing has inflicted undeniable pain on many workers in Massachusetts, and they deserve the Commonwealth’s full support making a transition to more viable jobs. But simply paying them to run horses in front of ever-shrinking crowds — at Suffolk Downs, in New York, or anywhere else — is not a long-term economic policy.

A review of the fund’s work by The Eye and WBUR public radio has found scant gains in breeding race horses, a schedule of racing that continues to be limited, and growing infighting among industry factions that has tried the patience of the fund’s overseers.

And I wrote in 2014 that the legislature would come for the RHDF.

Much like last year’s revised split that increased standardbreds’ share of the RHDF from 25% to 55% — Plainridge is running 125 days with average daily purses of $60K and a $250,000 stakes race in 2017 thanks to the boost — the proposed appropriation in the 2018 budget bill is being sold as a temporary way to put the fund to use — it’s for one fiscal year only — except that legislators, whether or not the budget passes as currently written, aren’t likely to forget that the RHDF money is there. The fund will become an even more tempting target for raids when the Springfield MGM casino opens in 2018 and a percent of its revenue begins to swell the RHDF.

New England HBPA executives promise to fight the proposed appropriation:

The New England Horsemen’s Benevolent and Protective Association, for example, makes the case that the money in the fund was intended to promote horse racing. What better way to promote horse racing than to promote a horse park with a track, officials said.

“When we look at that money in the Horse Race Development Fund, we see 1,000 jobs and the preservation of open space,†said Paul Umbrello, executive director of the horsemen’s association. “We will fight the transfer.â€

The NEHBPA continues to push their horse park plan; they propose to build a new racetrack and equestrian center in Spencer, a small town in central Massachusetts that’s off the Mass Pike but more than an hour from Boston. It’s a longshot. The Boston Herald blasted the plan a few weeks ago:

Now, silly us for raising a question like this, but if Suffolk Downs couldn’t make a go of thoroughbred racing a stone’s throw from downtown Boston, why on earth would the state want to invest its money in such a venture, say in maybe a town like Spencer?

It was, after all, Sen. Anne Gobi (D-Spencer) who filed a bill to divert money from the fund to a horse race park, while acknowledging that the racing industry is “on life support.â€

“This is an opportunity to support the entire industry,†she added. “We have to do something because it’s going and once it’s gone it’s not coming back.â€

And calling horse racing an “industry†does not make it so.

“We just want to say we want to take X percentage of that fund to build and support, as a bridge gap, the horse park,†Umbrello said. “Once we’re up and running it’s going to be self-sufficient.â€

Like we’ve never heard that one before!

Until lawmakers find a better use for the racing fund it will continue to attract nutty schemes like this one.

(My initial reaction to the NEHBPA plan when it was laid out last summer.)

The Massachusetts Gaming Commission declined to comment earlier this week, but chairman Stephen Crosby told the Globe last month that while:

he supported legislation that would reform the horse racing industry and give it a better chance of success in Massachusetts … taking away the fund would be the “death knell†for racing in the Commonwealth.

The death knell is sounding — the obstacles to the NEHBPA horse park are substantial, Brockton is not viable, and the state of the larger racing industry is against new construction or a new track operator entering Massachusetts.

8:00 PM Addendum: The NEHBPA pitched the horse park to reporters in an event this afternoon, Bruce Mohl reports in CommonWealth:

Brian Hickey, the association’s lobbyist and the host of Thursday’s presentation, said the group would like to see the law changed so the money in the Horse Race Development Fund could be used to directly support the state’s horse-racing industry. He estimated a couple hundred thousand dollars would be needed for the horse park feasibility study, and indicated more of the money would be needed if the horse park itself moves forward. He said revenues from simulcasting races from around the country could also be used to support the park.

More to come …

If you know the name Carlos Figueroa, you’re probably a New England racing fan. The trainer most associated with the defunct Massachusetts fair circuit died at age 88 on Tuesday at his home in Salem, New Hampshire. He had been recently ill. “His wife, Pearl, reportedly went to wake him, but could not.”

You could call Figueroa “colorful” — he had a flair for attracting attention wherever he went. Lynne Snierson passes along a characteristic story:

[Michael] Blowen, who labored in the barn for two years without ever seeing a paycheck, has many fond memories of his former mentor and holds him close in his heart.

“We have a horse here at Old Friends named Summer Atttraction, who I think just turned 23, that I owned. Carlos ran him as a 2-year-old in a two-furlong maiden race at Suffolk Downs in a four-horse field in 1997 on a big day. One of the other horses was owned by Jim Moseley (Suffolk’s late track owner and a prominent owner and breeder) and that horse cost over $200,000. Summer Attraction, whom I paid $5,000 for, won.

“So Carlos decided to next run him at Saratoga in the Sanford (G3). The race came up so tough that Favorite Trick (eventual 2-year-old champion and 1997 Horse of the Year) scratched out of it.

“In the paddock, the reporters all wanted to talk to Carlos even though Nick Zito, Wayne Lukas, and the other big-time trainers were there with their horses. Carlos told them, ‘If my horse wins, they’re going to rename the race Sanford & Son.’ My horse ran two furlongs and stopped cold. That story sums up The King.”

Blowen* captured Figueroa for the Boston Globe in 1982:

Trainer Carlos Figueroa, wearing a panama hat and a red polo shirt, is standing on top of a yellow tractor on the infield shouting at the top of his lungs, “Quatro, quatro, quatro,” as the horses in the eighth race at the Three County Fair in Northampton turn for home.

This is no ordinary race. It is the second leg of the Lancer’s Triple Crown, a series of races running from late August through late September that is as important to Figueroa as the Kentucky Derby, the Preakness and the Belmont are to Woody Stevens. And the horseman is trying to scream home his entry, Icy Defender, No. 4.

“Of course this race is important,” said Figueroa, as he strolled through the backstretch earlier that morning. “It’s the Triple Crown of the fairs. But I’m not in it for the money, I want the fame. Fame.”

Figueroa, who looks as if he could play Juan Peron in “Evita,” won the first leg two weeks earlier at the Marshfield Fair with Cheers n’ Tears, a 5-year-old who worked his way down the Suffolk Downs claiming ladder from $6500 on the Fourth of July to $3000 on Aug. 9. He received his trophy and had his picture taken by the track photographer just a few hours before the lady mud wrestlers and fireworks display took over the infield.

“I like records,” he said, while checking Cheers n’ Tears’ foreleg. “That’s why I want to win today. I have two horses in the race — this one and Icy Defender. I want to be the first one to win the Triple Crown.”

It was a horse named Shannon’s Hope that made Figueroa’s legend. Robert Temple tells the story in his book “The Pilgrims Would Be Shocked“:

… in 1963 Figueroa entered … Shannon’s Hope a total of eight times in 13 days and won five straight at distances from about 5 furlongs to about 6 1/2 furlongs.

The saga of Shannon’s Hope began August 12 when he finished fifth at the Weymouth Fair. The next day he finished third and two days later he was fourth. Then Shannon’s Hope began his hot streak. He won closing day at Weymouth on August 17 and moved to the Marshfield Fair on August 20 where he was a five length winner. He then won at Marshfield on three successive days (August 22-24) by a total of nine lengths.

Talk about durability. Shannon’s Hope ran a total of 309 races, winning 29 of them for total winnings of $39,848. When I asked Figueroa … why he entered Shannon’s Hope so often he replied, “He just like to run, run, run.”

In 1999, the trainer was suspended by the Suffolk Downs stewards for 90 days and fined $500 after a horse named Watral’s Winnebug tested positive for cocaine. The suspension was later shortened to 45 days by the state racing commission. Figueroa defended his innocence, telling the Globe:

“I know how to train horses,” said Figueroa, who was represented by attorney Frank McGee. “I don’t need cocaine to make horses run. I’m a good horse trainer. Cocaine is no good to me. Horses run on good food, a good trainer, and a good jockey.”

The state racing commission cited his reputation and record — he had never been suspended before — as a reason for reducing his days. “I don’t think he had anything to to do with [the positive],” said one of the commissioners.

Figueroa, “a fixture at Suffolk since the 1950s,” started his last horse at the East Boston track on November 13, 2010. His career stats on Equibase only go back to 1976 — between that year and his retirement, he won 846 races from 9,841 starts, earning more than $4.1 million.

For anyone who knew Figueroa at Rockingham Park and Suffolk Downs, the two main tracks at which he was stabled for decades, conversations with “King Carlos†often involved being shouted at in heavily accented English while trying to avoid his wildly gesticulating arms. He was forever phoning the Suffolk press box with good-natured demands for publicity and press coverage, and Figueroa liked to regale anyone who would listen with outlandish, difficult-to-document claims, like the time he allegedly singled all the winners in the very first Pick Six in the country when Rockingham offered the bet in the 1960s.

Here’s one more story:

When I announced Carlos won Trainer of the Week at Suffolk he called me and said "I am the trainer of the century!" https://t.co/O2uGiN22sj

— Larry Collmus (@larrycollmus) January 3, 2017

*In a 2000 column for the Globe, Blowen’s wife, Diane White, recounts the deal Figueroa made with him when he went to work for the trainer:

“You are a student at Figueroa University,” he told Michael, “and you are on scholarship.”

Copyright © 2000-2023 by Jessica Chapel. All rights reserved.